Books

The Stained Glass Window (2025)

The Family History as the American Story, 1790-1958

“At once narrative history, family chronicle and personal memoir… [a] luminous work of investigation and introspection.” –Wall Street Journal

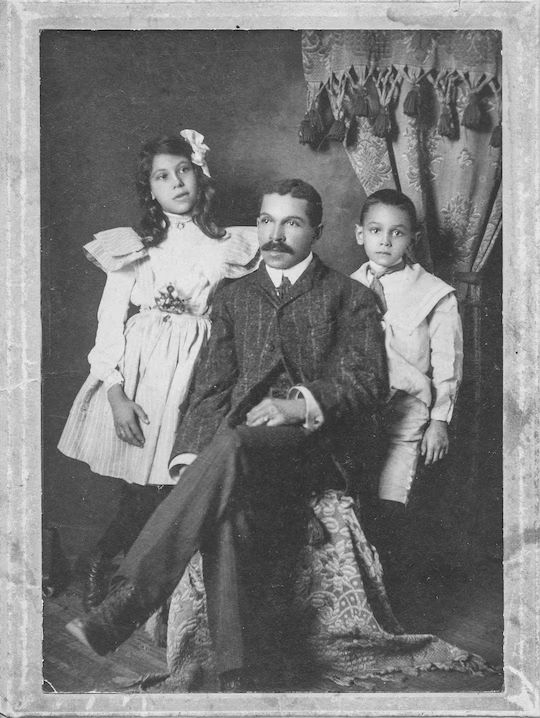

The Stained Glass Window tells the national story across the lives of four of my own family units: two of them white (Kings and Belvins); the third free and colored (the Bells): the fourth an up-from-slavery success (the Lewises). It starts by relocating the exceptionalist paradigm in the antebellum South---in a commonwealth based on caste, unfree labor, and staple crops (tobacco, rice, sugar, and above all cotton). It makes the central contention that we’ve looked in the wrong place and at the wrong race for the genesis of the American story. The vaunted paradigm American Exceptionalism has obscured the truth that what is truly exceptionalist about the exceptionalist narrative are the historic exceptions to it---notably , people of color.

It contends that the good news is the emerging historical revisionism upending the master narrarive of Jeffersonian/Jacksonian democracy with its unrivaled industrial takeoff, its robust middle classes gloriously replenished by hardworkingimmigrants, its eschatology of white merit. The new 1619 narrative shows that American slavery functioned as a vast, efficient concentration camp from which flowed the enormous wealth that underpinned the commercial and financial paramountcy of New York and Philadelphia and the rise of the industrial north. The success of my book is that it wraps the lives of these kings, Belvins, Bells, and Lewises around almost two hundred forty years of North American history. TheStained Glass Window claims to be an exceptional book not only, or not merely, in that explains macro-history as family history. It is unique in that the book’s author tells four stories about his own origins within the folds of the antebellum slavery project and then of the long national separate-but-equal aftermath whose inconclusive end has guaranteed our inconclusive present.

Press for The Stained Glass Window

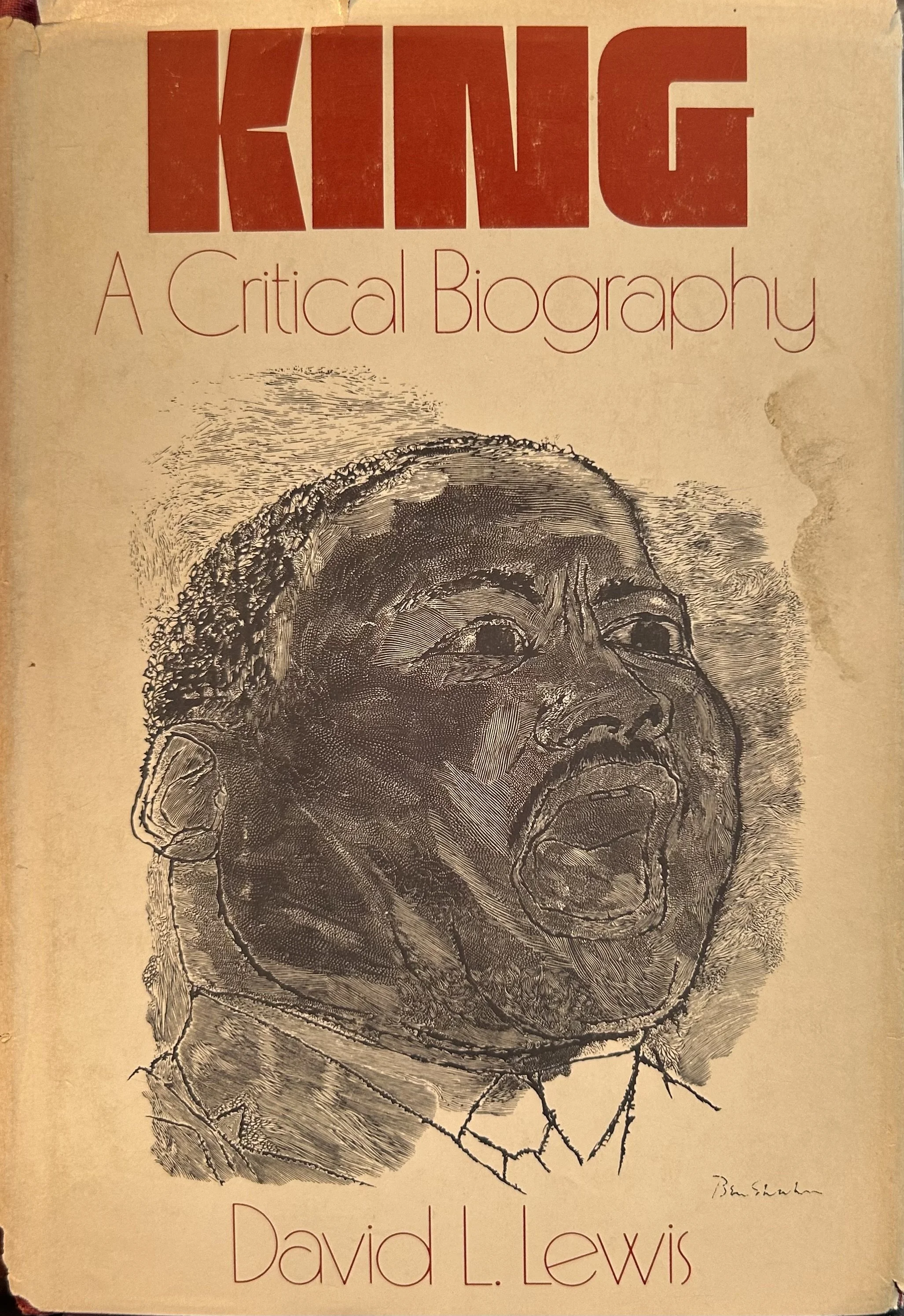

A young black historian has written the first in-depth, ciritcal biography of Martin Luther King Jr.

David L. Lewis has assesssed Dr. King’s career as a political leader with the thoroughness and detachment that are usually found only in studies of the great political figures of the dim past.

In his lifetime, the real Dr. King was often lost in the center of melodramatic events, and, since his assassination he has become an untouchable legend to millions of people. King: A Critical Biography restores the fallible baptist preacher-turned-political-leader, assesses all his failures (in Albany, Georgia, in Selma, and in Chicago), as well as his triumphs (from the Montgomery Bus Boycott to the Nobel Prize), and, in the end, shows us that this vulnerable human figure was far more impressive than the legendary hero-saint whom black militants of professor Lewis’s generation nicknamed “De Lawd.”

The Martin Luther King who emerges as a man surprised by historical circumstance, a leader partly manufactured by the news media and intimidated by them, groping uncertainly for a viable leadership style and yet, finally, growing to the full mastery of his international renown to such an extent that, ultimately, he came to surprise and intimidate many of his backers and promoters.

The final chapters of this complex life story tantalize us with the portrait of an increasingly disillusioned Martin King deciding not to lead a Poor People’s March on Washington, bewildered by the attention giving to the Black Power exponents, more bewildered by the hostility of Lyndon Johnson, and yet moving haltingly to accept a mandate that no other black leader dared consider—that of a spokesman for the poor of all races and against the Vietnam War.

This is controversial conclusion—many political commentators saw Dr. King as finished, unable to keep up with the younger militants—but professor Lewis makes a convincing case that MLK may well have been on the threshold of his real life’s work when he was assassinated.

Professor Lewis undertook this biography as an exercise in contemporary history, but it became “a passion for comprehension of the true significance of Martin Luther King and through him something of the nitty-gritty reality of blackness—collective and personal—in America.

The Dreyfus Affair began with the persecution of Alfred Dreyfus, the French Army’s most promising Jewish officer, who was falsely accused of passing as the cause célébre of the nineteenth century, the Affair not only of France but of the world, an event that was eventually to cause mass protests in Europe and America, produce Emile Zola’s ringing J’Accuse, and involve most of the leading international figures of the day.

Even today, this story of high drama that almost caused the downfall of a government is startingly relevant. For Prisoners of Honour tells how ambitious government officials framed Alfred Dreyfus as a traitor, raising anti-Semitism to a national passion, and then offered ‘national security’ as the reason for covering up the crime they had committed, until the nation’s leaders, military and civilian, came to believe that the revelation of the truth might cause the government’s downfall and therefore bring dishonour to France.

As they became ‘Prisonors of Honour,’ so did the object of their persecution. No man would seem a less likely hero than Alfred Dreyfus— ambitious, officious, stiff and formal. But he was also a man of extraordinary courage. Convicted of high treason, publicly degraded, torn frmo his family and sent to Devil’s Island, he remained a patriot determined to have his innocence proclaimed so that he could restore the honour of the Army and the country he loved. Because of the efforts of a few courageous journalists, his brother Mathieu, some of the nation’s leading intellectuals and politicians, including members of the Senate, Alfred Dreyfus and justice - the man and the cause - finally triumphed.

District of Columbia: A Bicentennial History (1978)

When Americans think of Washington, D.C,. their first images are likely to be of marble statues, bombastic orators, and bureaucratic red tape. This Washington of government and politics, author David L. Lewis writes, has obscured an urban world of rich cultures and competing groups that make up the real city and give it a character of its own, apart from tourist sites and national politics.

Beginning with Pierre L’Enfant’s grand design in the days of George Washington, the city came to have ‘magnificent distances’ and ‘magnificent intentions.’ But its slowness in realizing expectations also made it what one wag called a ‘low-budget Constantinople,’ and its magnificent distances tended historically to be social and economic as well as visual, between groups of people as well as between places, producing frustration for permanent residents, particularly those who sought self-government.

Lewis writes about those who truly have lived in the city rather than just those who have sojourned politically in the Federal Triangle and on Capitol Hill. He examines also the city’s art, journalism, and internal politics, along with the changing nature of its many distinct neighborhoods, and he considers the special meaning of the city historically for black Americans, who are now its racial majority.

This look behind the marble curtain of our national capital will be of great interest to all Americans, whether they come to tour, to politic, to live.

They were years of tremendous optimism in Harlem—the decade and a half following World War I, when Langston Hughes, Eubie Blake, Marcus Garvey, Zora Neale Hurston, Paul Robeson, and countless others began their careers; when Afro-America made its first appearance on Broadway; when its musicians found new audiences of the chic in search of the exotic in Harlem's whites-only nightclubs; when at one end of the social scale riotous rent parties kept economic realities at bay, while at the other A'Lelia Walker and white dilettante Carl Van Vechten outdid each other with glittering "integrated" soirées.

When Harlem Was in Vogue makes us feel the excitement of those times—and recaptures their intoxicating hope that black Americans could now create important art and compel the nation to recognize their equality. David Levering Lewis shows how black intellectuals embarked on a systematic program to bring artists to Harlem, conducting nation-wide searches for black talent and urging WASP and Jewish philanthropists (‘Negrotarians,’ in Zora Hurston’s phrase) to help support writers. He re-recreates the hot-house atmosphere in which ‘almost everybody above 125th street seemed to be writing for The Crisis, Opportunity or American Mercury, to be under contract to Boni & Liveright, Harper & Brothers, or Knopf.’ He introduces us to the flowers of that environment, some undeservedly forgotten, and shows how the program’s complex demands on writers—to reconcile art and propaganda, to attract white readers without reinforcing insulting stereotypes—ultimately sapped the energy of all but a few. We see Jessie Fauset’s novels about Harlem’s elite dismissed as boring by white critics, and the first book by a black writer to reach the best-seller lists, Claude McKay’s Home to Harlem, repudiated by black reviewers. And yet we understand that at the time the contradictory purposes, the bitter quarrels and broad humor they inspired, all contributed to the movement’s vigor.

To give us this book—the first to cover all aspects of the Harlem Renaissance and assess its actual achievements—David Lewis immersed himself for years in the literature and journalism of the period; tracked down and interviewed dozens of survivors; ransacked libraries and attics for unpublished letters and fascinating photgraphs. When Harlem Was in Vogue reminds us just how important the Renaissance was, and is—this movement which sprang up in Harlem but lent its mood to he entire era, and whose after-effects even now add immeasurably to the richness and character of American life.

Before 1870, the abandoned Egyptian fortress at Fashoda, on an obscure juncture of the White Nile, meant little to the outside world or, indeed. to most Africans. But suddenly, because of emerging rivalries between the Western powers, the rise of European colonialism, and its own strategic location, Fashoda became the focal point of an intense and bloody campaign involving England, France, Belgium, Germany, and Italy. This struggle also, unwittingly gave rise to a burgeoning resistance movement on the part of Black Africa—a movement that would culminate in the independence rebellions of the twentieth century.

Based on a wealth of previously unpublished documents, The Race to Fashoda tells intense, fascinating detail the story of Europe's incursions into Africa in the nineteenth century—and, for the first time, tells it from the perspective of the Africans themselves, many of whom were waging an arduous, often successful war against encroachment. Along the way David Levering Lewis demonstrates how the race to Fashoda, one of the most grueling episodes in the "Scramble for Africa," fostered the European political tensions that would lead inexorably to World War I and forever change the face of the Western world.

Here is a story as complex and stirring as any adventure tale, with a cast of characters to match: the driven, manipulative explorer Henry Mort on Stanley, who slaughtered thousands for the benefit of the front pages back home; African resistance fighters Tippu Tip and Samori Ture among the first to organize their compatriots against the European onslaught; Captain Jean-Baptiste Marchand, the consummate career officer, who fought the Africans, the British, and his country's unstable political climate to be the first to reach Fashoda—only to be ordered, once there, to hand it over to the British; Herbert Kitchener, Marchand's great rival, whose ingenious railroad brought him closer and closer to victory as the race drew to its climax; Abdullahi, the Sudan's xenophobic khalifa, who paradoxically found himself ruler of the continent's most contested piece of real estate; King Leopold II of Belgium, who pursued his share of the Congo with the sly acquisitiveness of a spoilt child; the shrewd Ethiopian monarch Menilek II, who swiftly learned how to use European vanity and conflicting interests to his own advantage; and the enigmatic Austrian Jew Eduard Schnitzer, who, as "Emin Pasha;" retreated into the jungle and commanded a private native army with all the resourcefulness of Conrad's Mr. Kurtz.

With its dramatic reconstructions and provocative viewpoint, The Race to Fashoda will stand as an insightful, compelling addition to our understanding of this key moment in modern history.

The hypnotic Old Testament voice of W.E.B. Du Bois thunders out of David Levering Lewis’s monumental biography like a locomotive under full steam:

"We claim for ourselves every single right that belongs to a freeborn American — political, civil, social; and until we get these rights we will never cease to protest and assail the ears of America. The battle we wage is not for ourselves but for all true Americans.”

Premier architect of the civil rights movement in the United States, W.E.B. Du Bois was a towering and controversial personality—a fiercely proud individual blessed with the language of the poet and the impatience of the agitator.

Eight years in the researching and writing, this compelling, lucid, and subtle portrait treats the early and middle phases of a long and intense career—a crucial fifty-year period that demonstrates how Du Bois changed forever the way Americans think about themselves.

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois was born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts in 1868, three years after slavery was outlawed; he died ninety-five years later on the eve of the historic civil rights March on Washington. Du Bois’s years as exemplar for an entire race are chronicled here in vivid detail: his childhood in “the hills of New England” (a period that assumed mythic proportions in his later writings); his studies at Fisk, where he entered the African-American world, and at Harvard under William James and George Santayana (he would return to Harvard to become the first African American to win a doctorate there), and at the University of Berlin; the rise of the Talented Tenth, and the establishment of the NAACP; the Niagara Movement for civil rights; the mounting tension between Du Bois and the great accommodator Booker T. Washington; his sparring with Carnegie and Rockefeller and rejection of their educational agenda for black America; the success of his pioneering and provocative books, especially The Souls of Black Folk; the founding and editing of the fiery and galvanizing journal The Crisis, from whose heated pages scholarship and majestic indignation thundered and flashed across the land for a quarter century; the leadership of the Pan-African movement; World War 1, and the brutal treatment of AfricanAmerican veterans that followed.

David Levering Lewis offers a magisterial and brilliantly rendered portrait of the man who, beyond all others, “grasp[ed] the implications of the struggle for racial justice, memorably proclaiming, at he dawn of the century, that the problem of the twentieth century would be the problem of the color line.”

Historian & Race: Autobiography and the Writing of History (1996)

From Eurocentrism to Polycentrism

To provide a context for understanding current race relations and the goals of the Civil Rights Movement, the editors ask distinguished scholars to reflect upon their careers and how personal experiences have influenced their scholarship. Prominent historians Dan T. Carter, Eric Foner, Darlene Clark Hine, Jacqueline Jones, David Levering Lewis, Leon F. Litwack, Mark D. Naison, George, and B. Tindall answered the call. They discuss issues such as the growing awareness of the racial oppression in the white south, the impact of the Black Power movement on young blacks, and the role of radical parents in shaping a sense of racial justice in their children. These essays provide personal glimpses into the intellectual development of some of the most important historians of the current U.S. experience.

In this final, magisterial volume, fifteen years in the research and writing, The Pulitzer Prize—winning biographer David Levering Lewis stunningly re-creates the second half of W.E.B Du Bois’s charged and brilliant career. Beginning with the return of World War 1 African American veterans to the riots and lynchings of the “Red Summer” of 1919 and ending with Dubois’s self-imposed exile and death in Ghana forty-four years later, Lewis charts the dramatic evolution of the premier architect of the civil rights movement from Talented Tenth elitist to internationalist and proponent of economic as well as racial democracy for all people of color. Based on original research on three continents, this richly-detailed volume of history alters our understanding of the culture and politics of race in the twentieth century.

Lewis chronicles the titanic struggle between Dubois and Marcus Garvey’s “back to Africa” movement and interprets the Harlem Renaissance as a civil rights enterprise masquerading as an arts movement that Du Bois, a movement impresario soon renounced in search of economic solutions to the race problem. After inspiring millions of Black and white readers through the NAACP journal The Crisis, Du Bois left the NAACP in a firestorm of controversy to pursue a politically risky course that took him inside Nazi Germany, the Soviet Union, China, and Japan as the major politics of the American century were taking shape. Leaving mainstream historians to absorb the seismic impact of his 1935 masterpiece Black Reconstruction in America, Du Bois looked increasingly to socialism in his search for race solutions after a postwar return to the NAACP that ended with his embrace of the Progressive Party politics of Henry Wallace, a deepening friendship with Paul Robeson, and an expanding circle of friends on the left. Federal indictment as a foreign agent and humiliation followed but failed to silence the prescient voice that would come to inspire new generations with its genius. Had he died at fifty, the great contrarian said that he would have been acclaimed. “At seventy-five, my death was practically requested.”

The New York Times Book Review wrote of the first volume of W.E.B. Du Bois, “One almost participates in the life.” With this masterly concluding volume, David Levering Lewis has restored the towering and flawed figure of W.E.B. Du Bois to a central place in modern American history.